The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) has recently released a draft memorandum for Modernizing the Federal Risk and Authorization Management Program (FedRAMP) on October 27th, 2023. There is currently a 30-day comment period until November 27th, 2023. Formal comments can be provided by navigating here.

The updated OMB Memo also rescinds the Federal Chief Information Officer’s December 8th, 2011 memorandum, and replaces it with the updated vision, scope, and new governance structure for FedRAMP. Which now brings us forward to today and the Modernizing FedRAMP Memo.

I will be assuming that the reader is quite familiar with the FedRAMP program, its goals, and generally has a few years of experience with the FedRAMP Program and the community.

Overall, the memo looks to push some overall change in the program to include some of the following key points — and we will be breaking each of these down in the following sections.

Memo Goals

Beginning with highlighting the key strategic goals and responsibilities the OMB Memo lays out:

- Lead an information security program grounded in technical expertise and risk management

- Rapidly increase the size of the FedRAMP marketplace by offering multiple authorizations structures

- Streamlining processes through automation

- Leverage shared infrastructure between the Federal Government and private sector

Key Insights and Findings

Some of the findings through the initial review and analysis include:

- Focus shift from IaaS providers to SaaS providers

- Prioritization of security control implementation based on real-world threat assessment/risk

- Additional emphasis on technical competency and risk management, specifically calls out FedRAMP needing the capability to sufficiently evaluate CSP’s security architectures (more on this later)

- FedRAMP is looking to scale dramatically to meet the scope of the cloud marketplace, allowing federal agencies to maintain a smaller IT footprint

- Implementation of different types of authorization strategies and structures for CSP providers

- Single-agency authorization

- Joint-agency authorization

- Program authorization

- Any other type of authorization

- Further emphasis on “presumption of adequacy” to lead to further reuse of authorizations

- Emphasis on automation, and FedRAMP to establish a process for automated intake of package reviews (The memo doesn’t call out OSCAL specifically, but definitely referring to it)

- The memo states a requirement for GSA to “establish a means of automating FedRAMP security assessments and review by December 23rd, 2023”

- Emphasis on sharing existing/shared infrastructure between both the Federal Government and private sector

- Additional clarification on external cloud services which are considered outside the scope of FedRAMP

- Encouraging FedRAMP to further expand FedRAMP Ready to help small or disadvantaged businesses who may face challenges in accessing the federal marketplace

- Potential “Interim-Authority-to-Operate” (I-ATO “esque”) or “Preliminary” type designation/process allowing Federal agencies to pilot the use of new cloud services which don’t currently hold a full FedRAMP authorization (to not exceed 12 months)

- Establishing a process for accepting external cloud security frameworks and certifications (e.g., reciprocity)

- Advanced notice from Cloud Service Providers (CSP)’s for significant changes without requiring advance approval from the government

- Potential alternative implementation for FIPS 140-2 requirements or security architectures aligning with latest

- Potential for “ad-hoc”/”out of band” “red-team” assessments to be conducted on any CSP at any point during or following the FedRAMP authorization process. This may or may not be part of the defined “Special Review”

- Encouraging FedRAMP to seek input from CSP’s to maintain a agile deployment lifecycle process which doesn’t require advance government approval — but ensuring the government still has visibility

- The FedRAMP PMO is to establish a standardized level of Continuous Monitoring (ConMon) support

- FedRAMP should leverage government-wide tools and best practices for enhancing ConMon — specifically CISA’s capabilities

- OMB to establish a Technical Advisory Group (TAG) to provide subject matter expertise to FedRAMP and advise on technical, strategic, and operational direction of the program — Federal employees only

- The FedRAMP PMO should continue to seek feedback from the industry on how to increase agency reuse of FedRAMP authorizations

We have a lot to cover — so let’s get started.

FedRAMP Background

Shift from IaaS to SaaS

The shift from IaaS to SaaS is expected. The initial FedRAMP ATO’s were primarily IaaS and PaaS, creating the base for the Cloud Service Providers to bring their SaaS to the market. There is a significant base for SaaS offerings and the shift to increasing SaaS is the next step to really ramp up the FedRAMP Authorizations and build out the cloud marketplace.

Prioritization of Security Control Implementation Based On Real-World Threat Assessment/Risk

Section 1, Background of the memo continues to highlight the importance of FedRAMP evolving and focusing its attention and engagement with the industry on security controls which lead to the greatest reduction of risk to Federal information and agency missions, grounding them in security expertise and real-world threat assessment.

Threat-Based Risk Profiling Methodology, released by the FedRAMP PMO on February 15th, 2022

FedRAMP PMO released a publication titled Threat-Based Risk Profiling Methodology back on February 15th, 2022 which was developed by the FedRAMP PMO, with representatives from the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Cybersecurity Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) in an ongoing effort to produce a threat-based approach to risk management for the federal government. The main focus of the methodology as stated in the document is:

The goal of this initiative is to enable agencies, Cloud Service Providers (CSPs), and other industry partners to prioritize security controls that are relevant and effective against the current threat environment. This leads to informed, quantitative-based risk management decisions in authorizing information systems for government use.

You can read the document by navigating here.

However, as far as the industry is concerned, after publication, not much has occurred in actual implementation of some sort of threat-based methodology for the FedRAMP Program.

This memo closes Section 1, Background by reminding us that FedRAMP must be an expert program that can analyze and validate the security claims of CSPs, while making risk management decisions which determine the adequacy of a FedRAMP authorization for re-use.

In summarizing the current landscape, it is evident that the FedRAMP program is at a pivotal juncture, emphasizing the integration of agile methodologies and a risk-management approach rooted in real-world threat intelligence. The commitment to utilizing threat-based analysis for security control prioritization is a forward-thinking move that aligns closely with the industry’s push for a more dynamic and responsive security posture. The release of the Threat-Based Risk Profiling Methodology by the FedRAMP PMO, in collaboration with CISA, laid the groundwork for this evolution.

However, the industry has noted a discrepancy between the release of such promising guidance and its tangible application within the program. The anticipation that followed the announcement of the Threat-Based Risk Profiling Methodology has been met with a sense of pause, awaiting its practical implementation. This delay has not gone unnoticed, and while the memo’s reiteration of a threat-based approach rekindles initial enthusiasm, it also serves as a reminder of the necessity for actionable follow-through.

As FedRAMP continues to evolve, it is crucial that these methodologies do not remain theoretical or relegated to the backlog of priorities. The expectation is not only for the publication of advanced frameworks but also for their swift and effective incorporation into the authorization process. The re-emergence of threat-based risk profiling in the latest memo is welcomed, yet it carries with it the industry’s call for a clear, expedited path to integration—one that moves from conceptual frameworks to operational realities. The promise of these advancements is contingent upon their execution, ensuring that the program not only stays abreast of current threats but becomes a standard-bearer for cybersecurity in the federal domain.

FedRAMP Vision

Section 2, Vision of the memo opens by defining the purpose of the FedRAMP program, which is, to increase Federal agencies’ adoption of and secure use of the commercial cloud, while focusing CSPs and agencies on the highest value work and eliminating redundant effort.

We have heard similar things of this FedRAMP vision over the years and it is safe to say, for the first several years no one in industry wanted to do anything with FedRAMP because it was thought to be another flash in the pan, another requirement that no one would care about and be gone. As we can see more than a decade later, FedRAMP is not a flash in the pan and has continued to gain traction. For industry, this means if you have not started down the FedRAMP path for your CSO’s you are late to the game. It is not too late, but the time for “waiting to see” has come and gone and if you are not jumping on the FedRAMP wagon then be prepared to be left behind. This point leads us to the next major topic, FedRAMP has to be able to scale more rapidly to handle the likely influx of CSPs who will be picking up (what we at bladestack.io like to call) the FedRAMP blade!

FedRAMP Must Scale

The memo continues to highlight the goal of the guidance is to strengthen and enhance the FedRAMP program, and the importance of the FedRAMP program needing to change to meet the scope of the cloud marketplace by scaling dramatically.

Total FedRAMP Authorized Services, dated October 30th, 2023

There has been a multitude of blogs, articles, podcasts and a treasure trove of posts on social media from LinkedIn to Reddit reflecting on the programs scalability (or therein the lack of) since FedRAMPs inception in 2011. Especially recently, as all sorts of new and innovative cloud solutions crop up routinely.

The memo indicates that for the FedRAMP program to achieve their capability to scale dramatically, the FedRAMP program has the following strategic goals and responsibilities:

Lead an Information Security Program Grounded in Technical Expertise and Risk Management

Bullet #1 under Section 2, Vision is to “Lead an information security program grounded in technical expertise and risk management”. The first goal/objective emphasizes the FedRAMP program is a security program which “should focus Federal agencies and cloud providers on the most impactful security features that protect Federal agencies from the most salient threats, in consultation with industry and security experts across the Federal Government.”

The goal continues and specifies “To do this, FedRAMP must be capable of conducting rigorous reviews and identifying weaknesses in the security architecture of cloud providers” and states that “FedRAMP is a bridge between industry and the Federal Government”.

Myself, industry voices, and the general community whom deals with FedRAMP frequently don’t necessarily believe the claim that “FedRAMP is a bridge between the industry…”. As many pointed out, interactions and dealings with FedRAMP, for the most part, feels equivalent to interacting with a walled garden, Ivory Tower, Drawbridge, or whichever similar analogy fits your tastes. FedRAMP must be more open to interactions and working with the industry and not immediately be dismissive to industry voice. I believe further transparency from FedRAMP will go a long way to aide and scale FedRAMP.

An example of the type of transparency I’m referring to includes, but not limited (all of which I’ve voiced and advocated for since the inception of FedRAMP) is to continue to provide more technical-oriented guidance as FedRAMP did in the past.

We understand providing technical-level guidance is a careful balance, as architectures and implementations are case-by-case basis, but if FedRAMP provided scenarios grounded in real-life examples, with a few assumptions, and actually focus on the approach and methodology on how FedRAMP analyzes and determines the risk and how FedRAMP has come to the established guidance — I believe this type of transparency will help CSP’s at least attempt to understand the approach they must take when it comes to implementation.

For example, FedRAMP released the guidance below, Subnets, What They Are and Why They Matter on June 2nd, 2022. For the most part, the guidance covers subnetting — however the guidance touches on a particular nuance of a “first compute instance”.

The Subnets guidance released by FedRAMP indicates:

“What constitutes “publicly accessible” is sometimes misunderstood. The Joint Authorization Board (JAB) considers the term “publicly accessible” to include the first compute instance that can be accessed from outside the boundary. These components often handle tasks such as authentication, or delivering the first data back to a destination outside the boundary.”

The guidance continues to indicate:

“There can be several network devices between the first compute device and the boundary, such as firewalls, gateways, load balancers, and proxy servers.” and provides two potential threat/attack vectors out of several, including Intruder Access and Compromise of a Publicly Available Component.

Consider the implementation of a CSP who enforces SSO as the only method to access the AWS Management Console, thereby disabling direct sign-in via IAM Policies. Now consider SSO can only be done via the CSP’s VPN, which is dedicated to the FedRAMP enclave of the CSO. Once an administrator has been successfully identified, authenticated, and authorized, and uses AWS SSM to manage an instance, Is the implementation acceptable? Does the AWS Management Console constitute as a first compute instance? Why or why not?

Better yet, , and flat-out deny other CSP’s without much reason than “we’ve seen some risks in the past?” We simply are asking for more transparency, and FedRAMP must be willing to engage with the industry.

There is also a notion of challenging any guidance which FedRAMP provides, you are simply putting your authorization in jeopardy. I simply believe a more open dialogue and willingness to understand and work with the CSP will help both parties understand where each party may be coming from and come to a more mutual agreement.

The current impression and takeaway from most of our customers are “Be obedient, don’t challenge FedRAMP, and hopefully you don’t put your authorization in jeopardy.” Whereas I believe the only way we can grow as an industry is in healthy discussions grounded in wanting to better understand each other’s positions. This will also start building more trust that the FedRAMP PMO is willing to grow and evolve as the technology and CSO’s will evolve over time and not always sit back on the FedRAMP PMO mighty throne and act as the supreme ruler with knowledge of everything. Like CSOs, 3PAOs, Advisors, MSPs, etc., the FedRAMP PMO must constantly learn and evolve to remain relevant and secure.

however there is unfortunately a reason this stigma/stereotype exists. The second point which is concerning is the statement that “FedRAMP must be capable of conducting rigorous reviews and identifying weaknesses in the security architecture of cloud providers”. which we will dive into more later on. FedRAMP must not only be capable of conducting rigorous reviews, but to be capable, you must also be willing to grow and try to learn. As mentioned in my example, the current impression is we must take everything as gospel – and not challenge FedRAMP.

Rapidly Increase the Size of the FedRAMP Marketplace by Offering Multiple Authorization Structures

Bullet #2 under Section 2, Vision touches on the reality that thousands of cloud service providers exists and to date, we are only at 318 authorized CSPs. The memo further elaborates that “FedRAMP is expected to create and evolve multiple authorizations structures, beyond those described in this document, that provide different incentives and flexibilities to agencies to achieve these goals”. The memo provides examples on the types of authorizations the guidance is advocating for, which we will touch on later. For now, one of the strategies to dramatically scale the FedRAMP program is the goal to offer more types of authorizations which may aide organizations where a particular authorization may not necessarily fit the organization.

For cloud service providers deliberating the strategic value of FedRAMP authorization, consider the competitive landscape. Assess how many of your peers have secured a FedRAMP Authority to Operate (ATO). If your offerings are unique in having a FedRAMP ATO, this positions you at a distinct advantage. It’s akin to navigating the market with a head start: while others are gearing up, you’re already advancing towards your strategic goals with the credibility and trust that FedRAMP authorization conveys.

Streamlining Processes Through Automation

Bullet #3 under Section 2, Vision emphasizes the importance of automation, particularly with “establishing an automated process for the intake and use of industry standard security assessments and review”, and later on in the memo, further includes automation of not only security packages, but processes in general – which is hopeful.

The goal continues to highlight that automating the intake and processing of machine-readable security documentation and other relevant artifacts will increase the speed of implementing cloud solutions. While the memo doesn’t explicitly call out the Open Security Controls Assessment Language (OSCAL), they are most definitely referring to OSCAL. OSCAL is a set of formats expressed in XML, JSON, and YAML. These formats provide machine-readable representations of control catalogs, control baselines, system security plans, and assessment plans and results.

Later in the memo, the guidance lays out a requirement for GSA to “establish a means of automating FedRAMP security assessments and reviews by December 23rd, 2023. Which is only two months away as of this writing — as many other industry voices have pointed out, either the FedRAMP program has been actively working on the implementation of automation, or the language of “must establish a means of automation FedRAMP” is loosely defined, or FedRAMP will miss the deadline. Most of the industry believes it may as well be a combination or a mixture of the examples highlighted. We are hopeful that automation will indeed be a sticking point for FedRAMP as it will be critical in meeting the and continuing to grow the size of the FedRAMP Marketplace (discussed above). It is also careful to note that the current memo is in DRAFT, but the dates themselves are typically a good indicator on what the federal government is deliberating.

Leverage Shared Infrastructure Between the Federal Government and Private Sector

The last and final bullet point under Section 2, Vision is a departure from previous guidance and direction the FedRAMP Program overall has previously taken. The memo now indicates “FedRAMP should not incentivize or require commercial cloud providers to create separate, dedicated infrastructure for Federal use, whether through its application of Federal security frameworks or other program operations”. Which is quite a major change. The memo continues to state “The Federal Government benefits most from the investment, security maintenance, and rapid feature development that commercial cloud providers must give to their core products to succeed in the marketplace.” and finally closes the final bullet with “Commercial providers should similarly be incentivized to integrate into their core services any improved security practices that emerge from their engagement with FedRAMP, to benefit of all customers”

Again, a lot to take in and unpack — however as other industry voices have also pointed out, a separate Federal purpose-built solution also has merit and competitive advantages. Not to mention, after decades of being in the advisory space, we’ve seen for most CSP’s, developing a purpose-built Federal solution has been more straightforward to the organization as opposed to attempting to makeshift the CSP’s current solution to accommodate the public sector. On the other side of the coin, we’ve seen multiple CSP’s whom would benefit greatly with the new approach and guidance.

The question ultimately is and will be what the Federal Government’s risk appetite will be for shared infrastructure. The Federal Government is very accustomed to purpose-built Federal solutions, and assuming a FedRAMP authorized CSP is advertising shared infrastructure as part of their solution, this may be seen as a con as opposed to a positive in the public sectors lens, even though the new guidance points to leveraging shared infrastructure. This of course are my own thoughts and assumptions, for all we know, the Federal Government may be quick (maybe a better word is, willing) to adapt to the new guidance.

FedRAMP Vision Close-Out

JAB’s Sunset?

Section 2, Vision of the FedRAMP memo closes with a statement regarding the FedRAMP programs structure, which consists of two parts:

- The PMO, located within GSA and led by a Director, is responsible for providing a security authorization process that meets the needs of federal agencies, is reasonably navigable for CSPs, and complies with applicable laws and policies, including this memorandum.

- The FedRAMP Board, composed of Federal technology leaders appointed by OMB, provides input to GSA, establishes guidelines and requirements for security authorizations, and supports and promotes the program within the Federal community.

Take note of what is mentioned here, because later on we’ll touch on an interesting footnote which essentially implies the Joint Authorization Board (JAB) may potentially be dissolved, at least as far as responsibilities for performing any type of authorization, and may be consumed into the FedRAMP Board. This, of course, is full speculation and based on “reading between the lines”, only time will tell.

Scope of FedRAMP

Section 3, Scope of FedRAMP opens with specifying OMB is essentially responsible for establishing the scope of cloud computing products and services that may receive authorizations through FedRAMP. The guidance further indicates that Agencies must obtain a FedRAMP Authorization when operating an information system within this scope. “This scope” being the following:

- Commercially offered cloud products and services (such as Infrastructure-as-a-Service, Platform-as-a-Service, and Software-as-a-Service) that host information systems that are operated by an agency, or on behalf of an agency by a contractor or other organization; and

- cross-Government shared services that host any information system operated by an agency, or by a contractor of an agency or another organization on behalf of an agency.

The guidance indicates the scope is only applicable to information systems that process unclassified information and are not national security systems.

Cross-government shared services include the following footnote: “Whether a particular Federally operated service qualifies as a “cross-Government shared service” for these purposes will be determined by the FedRAMP PMO, consistent with any relevant policies or criteria established by the FedRAMP Board.”

I’ve written at lengths about shared services, including a the aims to provide approachable shared services/management layer concepts which can be adopted for organizations looking to implement and deploy highly scalable services whilst maintaining compliance across a spectrum of services and applications.

However, the context in which shared services is used in the memo seems to refer to the point made earlier, which is to leverage shared infrastructure or potentially a mix of the shared infrastructure across a joint-agency authorization (We’ll get to this shortly). However, leaving the determination up to FedRAMP is interesting — will FedRAMP be required to engage with the industry or enforced to be transparent on how determinations are made?

Out of Scope Services

Section 3, Scope of FedRAMP continues to lay out additional cloud services which are deemed out of scope for FedRAMP, which include:

- Cloud-based services that do not host information systems operated by an agency or contractor of an agency or another organization on behalf of an agency and;

- Services that are offered by a Federal agency but are not a cross-government shared service

Pause – say what now?

Quick pause, I’ve had a few folks ask “Exactly what is the scope here?”

Here’s a breakdown:

- Information Systems Operated by an Agency or Contractor of an Agency: These include any computer systems, networks, and data storage systems used by a federal agency or a contractor working for a federal agency.

- Another Organization on Behalf of an Agency: This refers to a third-party entity managing or operating information systems on behalf of a federal agency.

The passage states that any cloud-based service which does not host these information systems – essentially not being used by a federal agency, its contractor, or another organization on its behalf – is considered outside the scope of FedRAMP.

The essence is to ensure that cloud services used by federal entities have a standardized level of security and authorization to protect sensitive government data.

To synthesize, the scope of FedRAMP is primarily on cloud services hosting information systems used directly by federal agencies, their contractors, or third-party organizations acting on their behalf. Any cloud service not hosting such systems is deemed outside FedRAMP’s purview.

After breaking the scope down — it seems obvious, however the wording and language is quite common in the public sector for specificity.

Back to the Examples

Now that we have further clarified the language, the guidance continues and provides three examples of cloud-services which are excluded as the examples do not host an information system operated by an agency or contractor of an agency or another organization on behalf of an agency.

- Ancillary services whose compromise would pose a negligible risk to Federal information or information systems, such as systems that make external measurements or read information from other publicly available services

- These may include (but not limited to) weather monitoring systems, which provide measurements to weather, real-time or historical data on traffic conditions, public transit schedule services, air quality, water quality measurements, or publicly available statistical data such as demographics, economics etc.

- Publicly available social media or communications platforms governed under Federal agency social media policies, in which Federal employees or support contractors may or may not enter Federal information

- These may include Facebook, although under federal social media policies, federal employees or contractors may use it for a form of official communication, it’s primarily a public platform. Similarly, X (formally known as Twitter), Linkedin, etc.

- Publicly available services that provide commercially available information

- These may include Google Search, Bing, Amazon, Ebay, etc — any other service which effectively provides commercially available information.

- This is similar in nature to the Rolodex clause when it comes to the context of PII. OMB M-07-16, Footnote 6, establishes the flexibility for an organization to determine the sensitivity of its PII in context using a best judgment standard. The example provided in footnote 6 addresses an office rolodex and recognizes the low sensitivity of business contact information used in the limited context of contacting an individual through the normal course of a business interaction. Essentially, the Rolodex exception is limited to the following business contact information which can be found via search:

- Name (Full or partial)

- Business Street Address

- Business phone numbers, including fax

- Business email addresses

- Business organization

The FedRAMP Authorization Process

Section 4, The FedRAMP Authorization Process of the memo opens with a preamble about the FedRAMP program, how the program is not an endorsement of a commercial product, but by certifying that a cloud product or service has completed a FedRAMP authorization process or the award of a provisional authorization, FedRAMP establishes that the security posture of the product or service has been reviewed and is presumptively adequate for use by Federal agencies.

The memo continues, and indicates “if a given cloud product or service has a FedRAMP authorization of any kind, the Act requires that agencies must presume the security assessment documented in the authorization package is adequate for their use in issuing an authorization to operate, and that neither additional security controls nor additional assessment of those controls are required.” — the memo is continuing to drive home the presumption of adequacy which was brought in by the FedRAMP Authorization Act.

The memo continues to lay out that an agency can overcome this presumption if the agency can demonstrate it has a “demonstrable need” for security requirements beyond those reflected within the FedRAMP Authorization Package or that the information in the existing package is “wholly or substantially deficient for the purpose of performing an authorization” of a given product or service.

The memo specifies that the FedRAMP Director is responsible for deciding whether an agency’s additional security needs merit devoting additional FedRAMP resources and conducting additional FedRAMP authorization work to support the revised package.

Further, If the FedRAMP Director deems additional authorization work is needed, and “a new authorization is issued, the sponsoring agency must also document in the resulting authorization package the reasons that it found the existing FedRAMP package deficient.” the sentence following is interesting as it states “However, these instances should be uncommon, in keeping with this policy of presuming the adequacy of FedRAMP authorizations”.

The reason I find the sentence interesting is because much hasn’t been elaborated on or shared in terms of the strategies to ensure these instances remain uncommon. As most CSP’s are aware (including a handful of our customers), additional requests have continued to be common and a significant amount of work, effort, resources and calories are spent in justifying the “presumption of adequacy” to agencies. Granted, the presumption of adequacy language did not come into effect until the FedRAMP Authorization Act, however the Federal Government has been operating with the current mindset for quite some time and will be interesting to see how this changes.

The guidance continues stating “FedRAMP will establish a set of criteria for expediting the authorization of packages submitted by interested agencies with demonstrated mature authorization processes”, setting up the remainder of Section 4, The FedRAMP Authorization Act to highlight how FedRAMP is to accomplish the goal expediting the authorization process.

However, the distrust by the industry and agencies themselves are not completely baseless on accepting authorization packages carte blanche, as many are aware there are hundreds of organizations which will develop authorization packages by either freshly minted college students with no experience, technical writers whom weren’t involved in the development, architecting of a service offering, or simply copy and paste shops which deliver inadequate packages, essentially “check the box” packages.

Shameless plug, but if you have experienced this (as many of our customers have), this is one of the main reasons why bladestack.io exists in the first place.

The memo specifies “The FedRAMP Authorization process should not only require CSPs to demonstrate security capabilities that meet the expectations of Federal agencies but should also recognize the value of newer industry practices that offer improved security and/or compensate for controls that would ordinary be required.” — which is, again, quite a departure with the current mindset of how the program has been operating with, and the industry and I are most definitely interested in how FedRAMP with evolve and threshold will be for going “against the grain” on some of the security control implementations or processes which are seen as foreign to the Federal government.

At this point, I would like to believe I speak on the behalf of a majority of the industry whom have been in the space, that implying FedRAMP has been anything which resembles any sort of bridge with the Federal and commercial sector is just simply not the case. The sentence states, “Acting as a bridge between the Federal community and the commercial sector, FedRAMP is responsible for balancing risk and innovation when applying policies governing Federal agency operations, and helping agencies benefit from newer approaches to information security and technology.”

Authorization Types

The next part of Section 4, The FedRAMP Authorization Process starts going into the current FedRAMP authorization structures and the desire to add additional authorization types and structures. The memo states that “FedRAMP will support multiple types of FedRAMP authorizations” and specifies the following:

- A single agency authorization, signed by a Federal agency’s authorizing official, that indicates that the agency assessed a cloud service’s security posture and found it acceptable.These authorizations will be designed to enable an agency to safely use a cloud product or service in a manner consistent with that agency’s risk tolerances. The FedRAMP Director is responsible for ensuring that the authorization can reasonably support reuse by agencies with similar needs.

- A joint-agency authorization, signed by two or more Federal agencies’ authorizing officials, that indicates that the agencies assessed a cloud service’s security posture and found it acceptable.These authorizations will be designed to enable a cohort of agencies with similar needs to pool resources and achieve consensus on an acceptable risk posture for use of the cloud product or service. The FedRAMP Board and FedRAMP Program are encouraged to proactively identify, organize, and support agency cohorts to reduce their effort and expense in conducting joint-agency authorizations. The FedRAMP Director is responsible for ensuring that the authorizations can reasonably support reuse by other agencies that would benefit from using the product or service.

- Any other type of authorization, designed by the FedRAMP PMO and approved by the FedRAMP Board, to further promote the goals of the FedRAMP Program.

The memo emphasizes at the end of the day, “the FedRAMP PMO is responsible for ensuring that the types of authorizations described above successful achieve their goals, and for generally enabling Federal agencies to safely meet their mission needs.” and goes on to effectively say, (paraphrasing here) agencies are responsible determining the acceptable risk for their agencies, FedRAMP will oversee and work with agency to make risk management decisions and regardless of the type of authorization, FedRAMP is responsible for consistently assessing and validating the security claims made by cloud providers.

Here comes some of the interesting tidbits which I’ve noticed other analyses haven’t covered but I picked up by “reading between the lines” and we also had a few of our other customers asking us the same. We obviously cannot confirm if our interpretation of what we “read” between the lines is accurate or not, but nonetheless, I’m not the only who has picked up on some of the following elements. So let’s’ break them down!

Reading Between the Lines:

JAB’s Curtain Call?

The FedRAMP CSP Community from cloud.gov, also recognized this potential subtle send-off and communicated his thoughts to the group.

An interesting footnote under Section 4, The FedRAMP Authorization Process indicates the following in relation to joint-agency authorizations:

“The joint-agency FedRAMP authorization is similar to that of the FedRAMP Joint Authorization Board “provisional ATO” (JAB P-ATO) used under the prior FedRAMP policy structure. However, unlike a JAB P-ATO, multi-agency authorizations can be issued by any group of agencies that work with the FedRAMP Program. Existing JAB P-ATOs at the time of the issuance of this memorandum will automatically be designated as joint-agency FedRAMP Authorizations.”

My initial reaction was to immediately re-read the language, and low and behold, if you read the memo in its entirety, it most definitely seems like a nod to JAB’s departure and possible consolidation into FedRAMP and the FedRAMP board. Further, the memo states later “the FedRAMP board engages with the FedRAMP PMO and its processes as a whole and is not expected to participate in the approval of individual authorization packages”

Only time will tell – however we have yet to see how the new joint-agency authorization will play out and how they will be treated compared to JAB P-ATO’s, but most in the community are somewhat more hopeful in reducing the barrier to entry (even though it will most likely be minimal). Progress is progress.

Ad-Hoc “Red-Teams”?

Again, reading between the lines, a sentence which has somehow conveniently been glossed over is the one placed “nonchalantly” in the mix of things, which reads: “FedRAMP Reviews are not limited to reviewing documentation, any may direct that intensive, expert-led “red team” assessments conducted on any cloud provider at any point during or following the authorization process”.

The sentence has the potential to become a very large point of contention depending on how exactly FedRAMP will plan to enforce and implement this requirement. It almost sounds as if FedRAMP will have the authority to “willy-nilly” direct a red-team. If the reader is unaware, most red-team assessments are objective based and are designed to test your security against real-world attacks. You can read more about red-teaming here, an article written by Josh Tomkiel, one of our partners at Schellman or here by my dear friend Erik Dominguez at Emagine IT.

Needless to say, the industry and I are quite intrigued and are looking forward to how FedRAMP is planning to implement and/or enforce this guidance.

Rethinking FIPS 140?

Again, this hasn’t only been picked up by me but a few others in the industry — is the implication that FedRAMP may be rationalizing elements of the FIPS 140 requirements.

So, how are we coming to these thoughts? Continuing onwards from Section 4, The FedRAMP Authorization Process, the memo reads, “Cloud providers are increasingly using complex architectures and encryption schemes to guarantee confidentiality and integrity, and FedRAMP must be able to validate that relevant implementations are reasonable and appear to work as intended. The FedRAMP Director should draw on technical expertise across government and industry as necessary to ensure that appropriate teams can conduct these assessments.”

The statement above in combination with the following statement later in the memo where the memo defines roles and responsibilities, and indicates that NIST will “Assess and update standards and guidelines, as determined necessary, to keep pace with the evolving technology landscape and support the continued evolution of FedRAMP”.

To what extent the memo may be rationalizing some FIPS requirements (or if they even are) is up for debate, in the air and only time will tell. But I’ve had enough folks ask us about this to warrant a call out. This guidance continues to become more in-line with FedRAMP R5’s guidance for SC-13 where the FedRAMP PMO seems to be more accepting of Non-FIPS cryptographic modules due to either vulnerabilities, currently in the validation process (but doesn’t hold a CMVP or added as a POAM item)

FedRAMP Marketplace & Ready – Small Businesses

Section 4, The FedRAMP Authorization Process elaborates on what FedRAMP Ready currently is and ultimately specifies FedRAMP Ready should grow to “further explore FedRAMP Ready to help on-ramp additional small or disadvantaged businesses who may provide novel and important capabilities.” which is encouraging to hear, as in our line of work as FedRAMP/NIST advisory services, we have a number of potential small businesses interested in FedRAMP but are ultimately discouraged with the initial “on-ramp” costs/resources/calories needed — so we are very interested in how FedRAMP will implement additional measures to allow small businesses to participate.

The paragraph closes with touching on contracts requiring a FedRAMP authorization: “Similarly, to support a robust marketplace, agencies may in some circumstances require a FedRAMP authorization as condition of contract award, but only if there are an adequate number of vendors to allow for effective competition, or an exception to legal competition requirements applies.”

Preliminary Authorizations

The last paragraph under Section 4, The FedRAMP Authorization Process begins with touching on the goal of identifying more cloud services which could become FedRAMP authorized, and to aide in the goal that “FedRAMP will provide additional procedures for the issuance of a type of preliminary authorization that would allow Federal agencies to pilot the use of new cloud services that do not yet have a full FedRAMP authorization.” which I believe is a step in the right direction. The memo continues, “such a preliminary authorization would provide for use of the covered product or service on a trial basis for a limited period of time, not to exceed twelve (12) months, with the goal of more easily supporting a potential FedRAMP authorization”

As many others in the industry have voiced — if implemented properly, we can absolutely see a drastic increase in FedRAMP authorizations as this provides agencies the ability to evaluate if a product meets their needs, gets the CSP engaged with the Federal entity and potentially down the road to ultimately pursue a FedRAMP authorization. I presume FedRAMP will add some stipulations, (just a guess) but potentially something along the lines of if the agency has determined the cloud service to be satisfactory to have this information communicated to the CSP and the CSP must take some sort of formal action towards achieving a FedRAMP authorization, or other potential mitigations to disallow agencies from experiencing any gaps in service for when the trial concludes, as the footnote indicates.

Automation and Efficiency

Section 5, Automation and Efficiency opens with a bold, but encouraging (if diligently pursued) statement and timeline of “As part of a technology-forward program optimized for efficiency and consistency, FedRAMP processes should be automated wherever possible. GSA must establish a means of automating FedRAMP security assessments and reviews by December 23, 2023.”

Again, as many other have voiced, including the industry, this cannot be overstated — the timeline is very aggressive. Either FedRAMP will not meet the timeline, FedRAMP has been working towards a solution, or the language is loose enough for the FedRAMP program to “meet the mark” for the requirement. It may very well be a combination of all these factors, including the fact that the guidance is still in draft form.

The section continues with “To ensure that it meets that requirement, FedRAMP should, to the extent feasible, receive all artifacts in the authorization process and continuous monitoring process as machine-readable data, through application programming interfaces that support predictable and self-service integration between services operated by FedRAMP and by CSPs.”

As some are aware, our company, bladestack.io is comprised of engineers whom have previously worked at product companies which worked towards the goal of automating evidence/artifacts — a very challenging/complex problem which absolutely needs solving to this day. For reasons I won’t state here, as it’s another story for another day, the team disbanded at the previous company and thus reconvened at bladestack.io.

That said, as many other organizations are chasing the goal of “machine-readable” artifacts have realized, machine-readable artifacts are simply one part of a longer equation. Don’t get me wrong, automation for machine-readable artifacts is absolutely a critical step which is required. However, as many other organizations pursuing this goal have already realized — at the end of the day, there is still a treasure trove of artifacts/evidence which once retrieved via an automated machine-readable mechanism, still requires a significant amount of human involvement in evaluation and assessment to make an overall risk determination.

From the documentation side, automation via mechanisms such as OSCAL, is again, critical for us to be more efficient and effective. As mentioned previously, we have been behind the scenes at these companies, working on these challenges in our past lives and in our current daily tasks, and automation definitely makes things easier. But as any engineer who has worked in the cybersecurity space and FedRAMP (or anything remotely dealing with compliance) understands the challenge of having mechanisms in place to accommodate all potential “edge-cases/nuances” — it’s never ending and drawing a line in the sand from a product standpoint could potentially limit your service offerings feature-set. We can sympathize with the issue, as this is exactly a core issue we would typically run into.

Overall, it’s important to remember that this is a step towards a more efficient and effective future — and I don’t believe anyone will dispute that the direction the program is taking is much needed. I’m just stating that it’s a step — and obviously, as with anything in life, only more challenges and problems will arise for us to solve, and I’m excited for that future to arrive.

Another hopeful statement in the memo states “The FedRAMP PMO will also identify additional FedRAMP processes in need of automation to promote efficiency and effectiveness within the program, and facilitate broader access to FedRAMP artifacts for agency partners with a mission need”. and “Automating the FedRAMP process goes beyond technical implementation to procedural efficiencies as well”. As a process/self-improvement junkie can relate — improving even the most basic processes can have substantial long-lasting improvements.

Control Inheritance / Common Controls

The next portion of Section 5, Automation and Efficiency touches on further evaluation and being able to analyze control inheritance. The memo continues with “To accelerate the adoption of secure cloud computing products and services, FedRAMP must maintain an analysis of what controls can be shared between cloud products and services that rely on an underlying platform or infrastructure offering. FedRAMP will use that analysis to create guidance that streamlines authorizations for cloud services that use FedRAMP authorized infrastructure or platforms.

As previously mentioned, I’ve published a 70+ page technical white paper covering this very topic and the importance of understanding responsibility. If you’re interested in delving deeper into the nuances, you can read the whitepaper here.

The Risk Management Framework (RMF) in combination with NIST Special Publication 800-53 introduced Common Controls. NIST defines common control as “a security control that is inheritable by one or more organizational information systems” and the revised Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Circular A-130 defines common control as a “security or privacy control that is inherited by multiple information systems or programs.”

Common controls serve a very important purpose within the realm of information security compliance and operations. However, with the rapid proliferation of cloud-based information systems, there needs to be further clarity in the nomenclature as well as improved guidance regarding inheritance of common controls implemented within an organization versus controls implemented by an external entity such as a cloud service provider (CSP) — and better late than never, as it seems FedRAMP is moving towards better clarity on inheritance.

Existing Industry Frameworks

The last paragraph of Section 5, Automation and Efficiency touches on the fact many existing cloud offerings have met existing external security frameworks, such as HITRUST CSF (pick your flavor), ACSC Information Security Registered Assessors Program (IRAP), SOC2, and many others.

The last paragraph in essence, is referring to FedRAMP accepting and/or leveraging external cloud security frameworks and certifications in lieu of newly performed assessments, and even designing certifications which can serve as a full FedRAMP authorization, although particularly for lower risk product and services. What the memo is essentially hinting at, is reciprocity, although doesn’t state it outright. NIST defines reciprocity as:

Reciprocity: Agreement among participating organizations to accept each other’s security assessments to reuse system resources and/or to accept each other’s assessed security posture to share information.

The memo continues to provide some guardrails on how these processes should be implemented, to include FedRAMP to make risk management decisions on what controls are acceptable for which situation and for if there are any misalignment or gaps within the security control frameworks. Ultimately, the decisions and determinations made by FedRAMP must align and requirements established by the FedRAMP Board. Once again, reading between the lines essentially means, the FedRAMP Board would need to approve any risk determinations made by FedRAMP.

Continuous Monitoring (ConMon)

Significant Change

If you read too quickly, you may miss it… but Section 6, Continuous Monitoring opens with encouraging FedRAMP to “incentivize security through agility, and should enable Federal agencies to use the most current and innovative cloud products and services possible.” and the next part is critical, “FedRAMP should seek input from CSPs and develop processes that enable CSPs to maintain an agile deployment lifecycle that does not require advance government approval, while giving the government the visibility and information it needs to maintain ongoing confidence in the FedRAMP-authorized system and to respond timely and appropriately to incidents.”

Reading between the lines, a revamped Significance Change Request (SCR) process, which requires advanced notice, but doesn’t require advanced approval, which is quite a “significant” change — I couldn’t resist!

FedRAMP Significant Change Process Policies and Procedures, Version 1.0, Published August 28, 2018

The FedRAMP PMO released guidance back in August 28th, 2018 regarding significant changes which garnered quite some pushback, moans, tears, and angst, due to the guidance outlining what FedRAMP considered “significant changes” as examples, and essentially dropped the kitchen sink as part of the examples which obviously caused major turmoil with the industry and CSPs and which is why FedRAMP has the stigma of being a slow, convoluted and complex process for essentially the majority of CSP’s, as the modus operandi for most of these organizations “Release early, release often” — the guidance essentially dwarfed any attempt in doing so.

Although, not entirely the case, a competent advisor would be able to write your package and methods, processes for your package to reduce a significant amount of heartburn when performing any type of change, to almost to the point of the guidance becoming somewhat negligible. However, for most of the industry, ConMon can and is typically an uphill battle. Although, I have some reservations on precisely how FedRAMP plans to change course and implement a process for the program to allow significant changes to be less painful for the CSP.

A key element for the process to be successful, as outlined in the memo, is ensuring the government has the visibility and information to maintain assurance in the FedRAMP authorized service offering as the CSP performs these changes and the ability to respond timely to incidents.

ConMon Process

The memo continues with establishing responsibilities for the FedRAMP PMO, specifically to coordinate with the FedRAMP Board and CISA to developing a framework for ConMon that:

- Prioritizes agility of development and deployment by CSPs, to support automation and DevSecOps practices within the cloud ecosystem;

- Calls for advance notice from CSPs of upcoming security-relevant changes (significant changes) to the FedRAMP-authorized cloud product or service without requiring advance approval from the Government;

- Provides CISA technical data to understand risks and detect threats to agency information and information systems

- Avoids incentivizing the bifurcation of cloud services into commercially-focused and Government-focused instances. In general, to promote both security and agility, Federal agencies should be using the same infrastructure relied on by the rest of CSP’s customer base

- Establishes expectations of authorized CSPs regarding incident response procedures, communication and reporting timelines, and other process that help ensure the Government is protected from potential attacks on cloud-based infrastructure.

These are some major changes and requirements from the new memo, all of which, are welcomed. Especially the sentence following the list, which reads, “For all FedRAMP authorized products and services, the FedRAMP PMO will provide a certain standard level of continuous monitoring support to authorizing agencies”, which I believe should help alleviate a lot of repetitive work as we have many customers we support for ConMon, and multiple agencies have requirements for different processes. Although, we’ve managed to have these agencies follow our process for ConMon, lessening the burden on our customers, we still receive some peculiar asks from agencies during the ConMon process which has the potential to cause rework.

The process of how FedRAMP will set this standard level of monitoring support should be driven by analyzing and identifying the most high value/impact controls, which hopefully are driven by the threat-modeling methodology as stated previously. When the standard level of support is finalized, FedRAMP PMO will be responsible for providing this support to all agency customers of FedRAMP authorized services, so we will for sure see an increase in FedRAMP personnel.

Special Reviews

The next portion of Section 6, Continuous Monitoring indicates that the FedRAMP PMO may conduct a special review of existing FedRAMP authorizations, regardless of the type of authorization. And that the FedRAMP Board must approve the special review and require a timeline for the review to be completed to be associated with the review period.

However, If the special review is approved, the FedRAMP Director is to convene a technical working group from across the Federal government to perform the review. Essentially, within the timeline, the group will conclude and produce a report with their findings and/or recommendations which will be submitted to the FedRAMP Director for review and make the determinations of any changes which may be required for the CSP to maintain a FedRAMP Authorization.

These special reviews are often performed if something has cropped up during the ConMon process which typically occur to less-than acceptable authorizations packages which have “somehow” passed the authorization process and more competent individuals have flagged it. This is very typical for initially approved packages when FedRAMP was in its infancy, a handful of less than acceptable packages made their way through the process and FedRAMP has been slowly performing these reviews for the worst offenders.

The remainder of Section 6, Continuous Monitoring touches on if the FedRAMP PMO identifies or becomes aware of any vulnerabilities in a CSP with a FedRAMP authorization (most likely referring to through the ConMon support function), it will communicate that information to the CSP and impacted agencies, potentially making ConMon a bit more stringent and rigorous as it seems FedRAMP will be more intimately involved in the ConMon process.

Finally, the section closes out with the memo encouraging the FedRAMP program to be more resourceful and leverage other already established tools and best practices to enhance its monitoring capability, and specifically calls out CISA’s capabilities and share the relevant data and tools for monitoring FedRAMP’s product and services.

Roles and Responsibilities

Section 7, Roles and Responsibilities, is quite straightforward, however we will touch on a few things in particular. The section outlines and details of key government stakeholders which interact or make up FedRAMP. I’ve outlined them here with my comments inline.

The General Services Administration

GSA resources, administers, and operates the FedRAMP program and is responsible for the successful implementation of FedRAMP.

In operating FedRAMP, GSA will fulfill a variety of responsibilities including:

- Develop and implement the process for FedRAMP authorizations, in consultation with DHS

- Grant FedRAMP authorizations consistent with the guidance and direction of the Board, including program authorizations for cloud products and services that meet FedRAMP requirements and threat-based risk analysis

- Here the memo is referring to the threat-based methodology we discussed earlier

- Provide a standard level of continuous monitoring support for the highest-impact controls of FedRAMP products and services

- Again, the identification of the highest-impact controls should be determined through a combination of methods including the threat-based methodology described above

- Develop partnerships with Federal agencies to promote authorizations and reuse, and establish a secure, transparent, and automated process for enabling agency officials access to artifacts in the FedRAMP repository

- Here, the memo seems to be referring to the changes to OMB MAX which is occurring, in addition to the automation guidance laid out

- Consult with the Federal Secure Cloud Advisory Committee (FSCAC) as appropriate

- Proactively engage with the commercial cloud sector, to represent the priorities of the Federal agency community and maintain awareness of contemporary technology and security practices

- We will touch on #5 and #6 at the end.

- Establish systems that support automated, machine-readable processing of authorization materials, and drive adoption of relevant standards throughout the cloud ecosystem;

- Develop guidance, as necessary, for best practices in the procurement of cloud products and services, in coordination with OMB, the CIO Council, and the Chief Acquisition Officers Council;

- Establish, and submit to the FedRAMP Board for concurrence, metrics that measure agency participation in FedRAMP, the time and quality of each step of the initial FedRAMP authorization process and ongoing interactions with the FedRAMP program, and any other metrics requested by the FedRAMP Board or OMB to measure program health and follow up with agencies as needed; and

- Position FedRAMP as a central point of contact to the commercial cloud sector for government-wide communications or requests for information concerning commercial cloud providers used by Federal agencies.

We have a lot to cover, so let’s get started!

In today’s fast-evolving cloud landscape for FedRAMP, the Federal Secure Cloud Advisory Committee (FSCAC) plays a critical role in shaping the secure adoption of cloud computing within the government sector. With the goal to provide advice to the GSA Administrator, the FedRAMP Board, and agencies, FSCAC is at the heart of influencing how the program evolves.

Screenshot of the Federal Secure Cloud Advisory Committee (FSCAC) page dated 11/2/2023

However, I believe (amongst other voices in the industry) that it’s time to take a closer look at the representation on FSCAC. Currently, the deck seems to be stacked with larger companies, which could potentially overshadow the smaller, yet innovative players in the cloud space. There’s a growing concern that the valuable insights and agility of smaller businesses, defined by Section 3(a) of the Small Business Act, are not being fully tapped into. Small businesses often bring fresh perspectives and could contribute significantly to increasing the number of FedRAMP authorizations, ultimately diversifying the cloud services available to agencies.

Furthermore, it seems there’s a missing piece in this advisory puzzle— we believe having an independent voice from a consulting firm that works hand-in-hand with Cloud Service Providers (CSPs) whom are pursuing FedRAMP on a daily basis. And I may be biased here, but with the amount of feedback we receive as we are such a firm, the input would be extremely valuable. Such firms as ours have their fingers on the pulse of what CSPs face, including the intricacies of authorization processes, and could offer grounded, pragmatic advice to reduce associated burdens and costs from the initial stages.

In the spirit of continuous improvement, FSCAC is exploring several measures:

- Boosting Agency Reuse: Increasing the reuse of FedRAMP authorizations can streamline processes and cut red tape.

- Cutting Costs and Confusion: Reducing the cost and confusion surrounding FedRAMP authorizations for CSPs should be a top priority. Clearer guidance and streamlined processes could make a world of difference.

- Empowering Small Businesses: Encouraging more FedRAMP authorizations for products and services from small businesses not only supports the economy but also spurs innovation.

- Reducing Agency Burdens: Alleviating the authorization load for agencies can expedite secure cloud adoption and operational efficiency.

To really hit the mark, collecting feedback on compliance and implementation is essential, as is fostering communication among the stakeholders. Only by listening and collaborating can the FSCAC ensure that the path forward is inclusive, effective, and secure.

Now, with these considerations in mind, I believe FSCAC should reflect on its composition and processes. It’s not just about the big players; it’s about an ecosystem of ideas, solutions, and innovations that secure a resilient cloud environment for the federal government.

We also again see the memo encouraging that FedRAMP positions itself “as a central point of contact to the commercial cloud sector for government wide communications or requests for information concerning commercial cloud providers used by Federal agencies” — which as mentioned previously, FedRAMP in its current state, simply isn’t, and as encouraging as it may be to see the memo suggesting FedRAMP to position the program as this central point of contact, we will see later on, that the divide between Public and Private will most certainly continue to grow.

The FedRAMP Board

The introduction for the FedRAMP Board begins with describing the composition of the FedRAMP Board which are:

- The Office of Management and Budget (OMB), in consultation with the General Services Administration (GSA), appoints members.

- It includes at least one representative each from GSA, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), and the Department of Defense (DoD).

- Additional agency representation is determined by OMB.

- Board members are chosen for their expertise in areas such as cloud technology, cybersecurity, privacy, and risk management.

However, what caught my attention were the following key takeaways, paraphrased by me:

- Essentially the FedRAMP is intended to represent the entire Federal community

- The FedRAMP Board is encouraged to maintain consensus among its members when making decisions, as described above, for example, special reviews, decisions on how to engage industry, etc.

- Ultimately, processes must be in place by the FedRAMP board to ensure final decisions can be made in absence of unanimous support

Thus, the memo states the Board will:

- Provide input and recommendations to GSA regarding the requirements and guidelines for, and the prioritization of security assessments of cloud computing products and services

- In consultation with GSA, serve as a resource for best practice to accelerate the process for obtaining a FedRAMP authorization

- Establish requirements and guidelines for security assessments of cloud computing services, consistent with standards defined by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), to be used in determination of a FedRAMP authorization

- Establish and regularly update requirements for security authorizations of cloud computing products and services, including government-wide shared services, consistent with OMB policy and NIST standards and guidelines, to be used in the determination of FedRAMP authorizations

- Monitor and oversee, to the greatest extent practicable, the processes and procedures by which agencies determine and validate requirements for a FedRAMP authorization, including periodic review of agency determinations that existing assessments in the FedRAMP repository were not sufficient for the purpose of performing an authorization

- Essentially referring to those scenarios where an agency reviews an existing FedRAMP package for an authorized service and deems the package inadequate — FedRAMP will work to better understand how agencies are making these risk determinations to avoid additional duplicative work. As the industry is aware, this can happen quite often. However, there is also some merit to the statement, as there are agencies who have stumbled upon inadequate packages and pushed back, and rightfully so.

- Ensure consistency and transparency between agencies and CSPs in a manner that minimizes confusion and engenders trust

- Needless to say, the Industry and I are quite curious on what the FedRAMP program is planning to provide to further increase transparency, especially considering the next group which we will be getting to shortly…

- Perform other roles and responsibilities as assigned by OMB, acting through the Federal Chief Information Officer, with the concurrence of the FedRAMP PMO at GSA

In closing, the FedRAMP Board will also be responsible for establishing metrics in regards to the time taken and quality of FedRAMP authorizations.

Technical Advisory Group (TAG)

The “TAG” is what has ruffled quite a bit of the industry’s feathers — and rightfully so. OMB will be establishing a Technical Advisory Group (TAG) to, “provide additional subject matter expertise to FedRAMP and advise on the technical, strategic and operational direction of the program”

The memo indicates TAG’s goal is to provide additional methods for providing input across the Federal community into how FedRAMP functions and, “serve as an independent source for technical and programmatic best practices and insight”

Additionally, the TAG is supposedly be comprised of “six technical experts in cloud technologies, cybersecurity, privacy, risk management, digital service delivery, and other competencies as identified by GSA, with OMB concurrence.”

This brings us to a notable point: TAG members are to be exclusively federal employees. Considering the earlier reference to FedRAMP’s authoritative role, one must question the rationale behind restricting the TAG’s composition to only those within the federal workforce. The very premise of the federal government’s outreach to the private sector is recognition of the innovation and expertise that reside there. It stands to reason that the TAG would benefit from the inclusion of industry professionals who bring fresh perspectives and cutting-edge knowledge to the table. Further insights on this matter follow below.

I genuinely believe the establishment of the Technical Advisory Group (TAG) merits a focused discussion. The creation of the TAG by OMB is intended to augment FedRAMP’s pool of expertise and guide its technical, strategic, and operational direction.

It’s clear that the TAG’s mission is to inject a broader range of insights into FedRAMP’s processes and provide an independent wellspring of technical and programmatic best practices. This objective aligns with the need for a robust and dynamic framework capable of addressing the complexities of today’s cloud technology landscape, especially for FedRAMP.

The composition of the TAG, as stated, will include up to six specialists with expertise in key areas such as cloud technologies, cybersecurity, privacy, and risk management. These individuals’ roles are pivotal—they are tasked with shaping the contours of continuous monitoring practices and refining risk assessment methodologies for FedRAMP authorized services.

However, the decision to limit TAG membership exclusively to federal employees sparks a complex conversation. While federal employees undoubtedly bring valuable experience and insights, it is equally important to recognize the unique perspectives that professionals from outside the federal government can offer. Industry players, such as cloud service providers and cybersecurity firms, are at the forefront of technological innovation and often grapple with challenges that are invisible to the federal perspective.

By excluding these voices, there’s a risk of creating an echo chamber, (which we’ve undoubtedly have experienced with the current FedRAMP program) potentially insulated from the rapid advancements and ground-level realities of the tech industry. Engaging with industry experts can provide a fresh viewpoint, invigorate discussions with practical insights, and help ensure that FedRAMP stays at the forefront of technological and security trends.

As a company deeply immersed in guiding CSPs through the FedRAMP process, we at bladestack.io recognize the importance of diverse expertise. Our day-to-day experiences offer us an on-the-ground perspective that is both unique and critical to the evolution of frameworks like FedRAMP. While we appreciate the capabilities of our federal counterparts, we believe that a collaborative approach that includes industry stakeholders would enhance the effectiveness and relevance of the TAG.

In conclusion, while the formation of TAG is a commendable step towards strengthening FedRAMP, it is an opportune moment to advocate for an inclusive approach that leverages the collective intelligence of both federal and industry experts. Such a collaborative endeavor could be pivotal in ensuring that FedRAMP not only maintains but elevates its standards in our rapidly evolving digital age.

Agencies

Federal agencies responsibilities are straightforward with the exception of the ones outlined below with inline comments, each agency must:

- Upon issuance of an agency authorization to operate based on a FedRAMP authorization, provide a copy of the authorization-to-operate letter and any relevant supplementary information to the FedRAMP PMO, including configuration information as applicable

- Ensure authorization package materials are provided to the FedRAMP PMO using machine-readable and interoperable formats, in accordance with any applicable from the FedRAMP program

- Provide data and information concerning how they are meeting relevant security metrics, in accordance with OMB guidance; and

- Ensure that relevant contracts include the FedRAMP security authorization requirements with which the contractor must comply

Again, not explicitly stated but #2 is most certainly again referring to the automation which would be afforded by OSCAL. However, it’s worth nothing some agencies do have some level of machine-readable data in the form of eMASS, CFACTS for CMS and/or IASE to name a few.

Department of Commerce

The last role and responsibility outlined in Section 7, Roles and Responsibilities is for the Department of Commerce, specifically NIST. The memo states that NIST will:

- In coordination with OMB and CISA, review the underlying NIST standards and guidelines used by FedRAMP to identify and assess the provenance of the software in cloud services and products

- Assess and update standards and guidelines, as determined necessary, to keep pace with the evolving technology landscape and support the continued evolution of FedRAMP

- Monitor and review private sector information security practices to understand potential application

- Develop and maintain a machine-readable data standard to support automation of security assessments and continuous monitoring, as well as the automation of other artifacts or processes required by the Risk Management Framework for Information Systems and Organizations

Bullet #1 seems to indicate additional Supply Chain Risk Management and software transparency guidelines may be published by NIST as the memo calls for additional review of the existing material, and I most definitely suspect to include guidance around elements such as recommended approaches to Software Bill of Materials (SBOM) as that’s a major topic around software transparency as a whole.

Additionally, the last bullet, #4, is again referring to OSCAL automation, although not specifically but the memo is another component which is exerting more influence to the implementation of machine-readable data standards. As discussed previously, artifacts and evidence to a degree becomes quite a challenge — and organizations are working to solve these challenges as we speak.

Industry Engagement

The assertion that FedRAMP serves as a bridge connecting federal agencies with the commercial cloud marketplace is indeed a foundational principle of its mandate. The program’s mission to streamline the adoption of cloud services by federal entities while ensuring stringent security measures is well-articulated and theoretically positions FedRAMP as an enabler of efficient cloud adoption.

Yet, perceptions within the cloud service provider (CSP) community suggest a deviation from this envisioned role. As discussed earlier, the characterizations of FedRAMP as an ‘Ivory Tower’ imply a sense of exclusivity and inaccessibility that conflicts with the image of a facilitative bridge. It seems that for some, currently, FedRAMP appears more as a gatekeeper than a gateway.

The need for greater openness and a receptive stance towards industry input is not just a matter of good public relations; it is critical for the program’s ability to adapt and align with the rapidly advancing cloud market. The GSA and the FedRAMP Board’s engagement with industry partners should not be merely symbolic. Rather, it must be substantive, entailing a sincere willingness to integrate feedback and evolve policies and operations in response to the practical realities faced by CSPs.

In an environment where CSPs perceive compliance as an uncompromising directive rather than a collaborative process, the potential for innovation and improvement is stifled. It’s concerning when industry partners feel that challenging FedRAMP’s guidance might endanger their authorizations. An atmosphere that fosters open dialogue, where questioning and refining the status quo is encouraged, is fundamental for mutual growth and understanding.

It is also essential to address the operational concerns expressed by CSPs, such as the inefficiency of reporting identical information to multiple federal customers. The role of the FedRAMP PMO as a central information repository should alleviate such redundancies and contribute to a more cohesive federal cloud security strategy.

Ultimately, while there are instances of positive interaction, the prevailing sentiment indicates room for significant improvement in FedRAMP’s approach to industry engagement. To embody its role as a bridge, FedRAMP must evolve from merely conducting rigorous security reviews to embracing a growth mindset that values and integrates industry expertise.

A collaborative future where industry perspectives are not only heard but actively sought and considered could transform FedRAMP into the dynamic and responsive bridge it aspires to be, truly facilitating the flow of innovation and security between the federal and commercial sectors.

Implementation

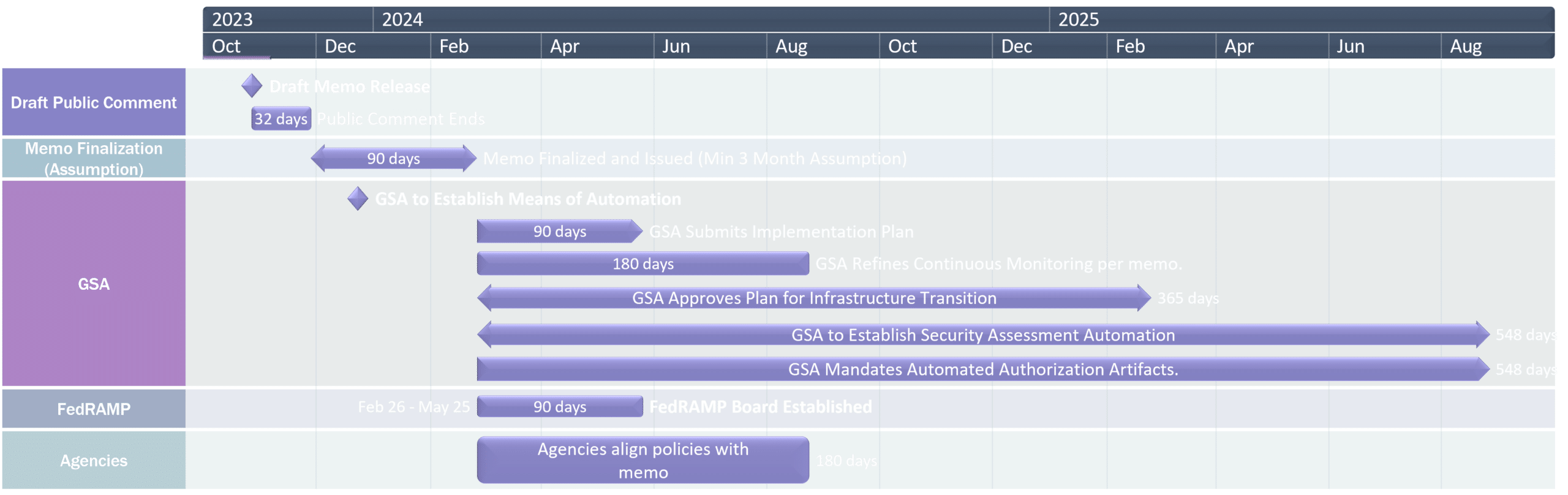

Finally, the memo closes with timelines of the implementations:

- Within 90 days of issuance of this memorandum, OMB will appoint an initial slate of members of the FedRAMP Board. The Board must, once constituted, approve a charter.

- Within 90 days of issuance of this memorandum and annually upon request, GSA will submit a plan, approved by the GSA Administrator, to OMB, detailing program activities, including staffing plans and budget information, for implementing the requirements in this memorandum.

- The plan will include a timeline and strategy to bring any pending authorizations or existing FedRAMP initiatives into conformance with the Authorization Act and this memorandum.

- Within 180 days of issuance of this memorandum, each agency must issue or update agency-wide policy that aligns with the requirements of this memorandum.

- This agency policy must promote the use of cloud computing products and services that meet FedRAMP security requirements and other risk-based performance requirements as determined by OMB, in consultation with GSA and CISA.

- Within 180 days of issuance of this memorandum, GSA will update FedRAMP’s continuous monitoring processes and associated documentation to reflect the principles in this memorandum.